Virtual Study Visit No. 1, 25.03.21

Tools and projects for participative budgeting (PB) and participative planning (PP) were the focus of the Interreg NW Europe ‘Better’ project’s first virtual, online study tour of the beautiful city of Nyíregyháza, Hungary. With a population of 120,000 and home to a number of multinational companies including: Lego, Bosch, Michelin and Electrolux, Nyíregyháza set out on its journey towards a digital economy in 2015 and has come on leaps and bounds since then. One of the methods the municipality has been keen to explore is participative budgeting in order to deliver a more democratic, transparent involvement of its citizens in decision making processes. The Hungarian team were keen to point out that participative budgeting would ideally involve face-to-face dialogue and continuous communication with citizens to build trust and transparency and help deliver successful results. The team showcased IT technological tools which could support PB and PP when face to face meetings become impractical. Such technology has provided a useful additional method of citizen engagement in pre-Covid and Covid times.

Urban Dialog

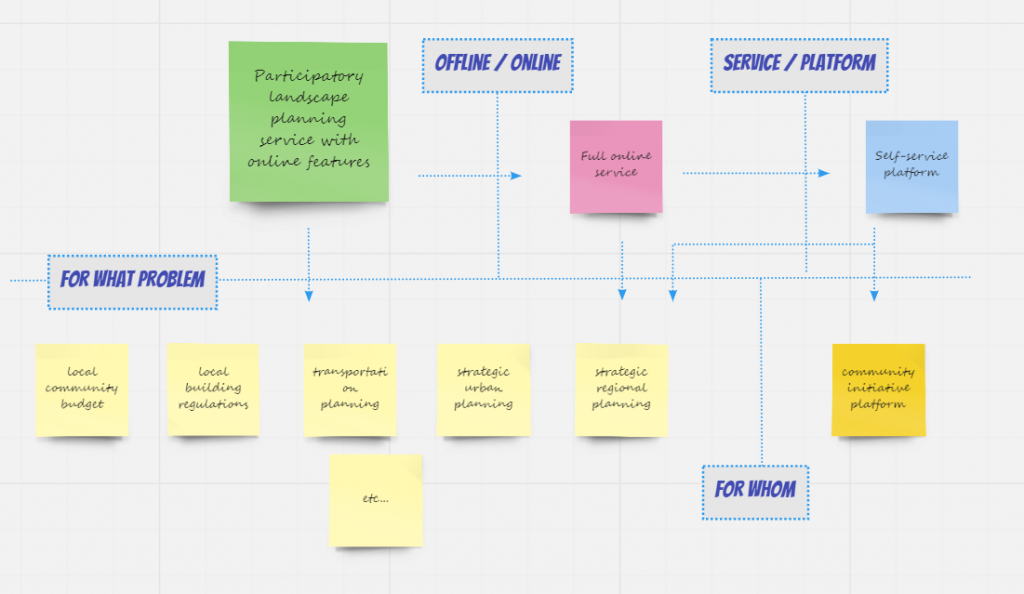

The Urban Dialog (UD) company developed an online social platform for urban development to help the Nyíregyháza municipality to boost the success of local citizen projects. The platform acted as an interface between companies, local government and citizens to trial a novel approach to neighbourhood development. Set up using seed money 6 years ago, the platform offered an alternative to the existing approach to PB.

Before the online platform was set up, local residents wanting to propose a local development/project idea would contact local government to register their request. The request was passed to the relevant department and then decision makers assessed the request based on whether the initiative provided a solution to a problem, had wider community benefits and had sufficient budget to support it. The budget for projects came both from local government and local businesses. The local residents were informed of the project upon completion. The weakness of the system lay in the lack of communication with the idea originator following the initial contact and the absence of consultation with local residents who would be impacted by the project.

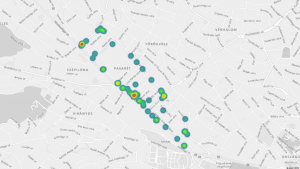

The solution to this communication gap came in the form of a platform devised by UD for participatory planning. It adopted GIS map technology to give residents the opportunity to upload photos and text with a description of the project they wold like developed in their locality. Residents registered on the platform are able to post comments, suggestions and improvements to the project as well as rate the idea. The site also hosts a survey for residents to complete which is linked to a GIS map to facilitate detailed feedback. Data from the survey is visualised in a heatmap to show which area projects are most popular. Feedback is given to survey participants to maintain the contributors’ trust and keep a dialogue open. Once the idea garners enough support, local government steps in to provide plans and ideas on how to develop the proposal. The whole process is transparent; users can see their idea registered and residents are able to express their support, concerns and questions about the project proposal. The platform has also been adopted by the municipality to increase engagement with the public when developing new planning proposals and has been particularly useful during Covid lock downs. The site openly displays differing viewpoints and this transparency has often led to a diffusion of potential conflicts.

The solution to this communication gap came in the form of a platform devised by UD for participatory planning. It adopted GIS map technology to give residents the opportunity to upload photos and text with a description of the project they wold like developed in their locality. Residents registered on the platform are able to post comments, suggestions and improvements to the project as well as rate the idea. The site also hosts a survey for residents to complete which is linked to a GIS map to facilitate detailed feedback. Data from the survey is visualised in a heatmap to show which area projects are most popular. Feedback is given to survey participants to maintain the contributors’ trust and keep a dialogue open. Once the idea garners enough support, local government steps in to provide plans and ideas on how to develop the proposal. The whole process is transparent; users can see their idea registered and residents are able to express their support, concerns and questions about the project proposal. The platform has also been adopted by the municipality to increase engagement with the public when developing new planning proposals and has been particularly useful during Covid lock downs. The site openly displays differing viewpoints and this transparency has often led to a diffusion of potential conflicts.  The Hungarian team stressed the importance of maintaining dialogue with residents over the course of project development. If consensus can be achieved and concerns are taken on board, fewer issues arise following the completion of the development. The new system brought an increase in participation in the planning process and has proven an invaluable tool whilst social distancing measures were in place.

The Hungarian team stressed the importance of maintaining dialogue with residents over the course of project development. If consensus can be achieved and concerns are taken on board, fewer issues arise following the completion of the development. The new system brought an increase in participation in the planning process and has proven an invaluable tool whilst social distancing measures were in place.

https://www.budapestdialog.hu/

Budapest District 14 – Sunrise project

Participative budgeting has not been a feature of Hungarian policy making in the past (largely due to a Communist preference for centralisation) and the Sunrise Sustainable Urban Neighbourhoods project signalled a new era of greater transparency and involvement of citizens in initiatives to improve the local area. Zuglo is a district in Budapest with a population of 120,000 people and was the target area for the project. The catalyst for launching such a participatory project lay in its European H2020 funding source. The external funding enabled the district mayor to take a risk and break from tradition. The first task of the project was to set up a grass roots board of local citizens with a non-hierarchical, liberal structure. The enthusiasm of the group resulted in meetings finishing as late as 2am in the morning! The board wanted to ensure that the residents’ concerns and ideas were registered, so they invited residents to co-create solutions. Each of the ideas was summarised in a document and disseminated to the local community both online and through leafleting to the local community. Online and offline voting took place to select three projects to be awarded a portion of the €65,000 budget. One of the initiatives was akiss and go drop off at school which helped to alleviate pollution from traffic build up in front of schools. Such was the success of the project that an additional two projects were funded from the municipal budget. What is incredible is that now 8 of the 23 districts in Budapest have adopted the participatory budget methodology and local administrations are now looking at how to include this methodology to relaunch the economy post Covid.

It will be interesting to see how PB and PP develops in Nyíregyháza and Budapest. Covid has been a catalyst for many citizens to engage with technology whether through WhatsApp neighbourhood support groups, online services or more sophisticated platforms such as Urban Dialog. The examples presented were novel and complemented more traditional methods of engagement. Continual communication and transparency were central to their success. Whether online platforms will completely replace more traditional methods of planning remains to be seen, as the digital divide and access to computer hardware for everyone is yet to be solved.

For further information, please contact: Heather.Law@birmingham.gov.uk